© LILA Foundation

E.P. Unny is a celebrated Indian political cartoonist. After an education in sciences, he published his first cartoon in Shankar’s Weekly, in 1973. Four years later, he becomes professional, first with the Hindu, before working with The Economic Times, and finally The Indian Express Group, where he is currently Chief Political Cartoonist. He is the author of several graphic novels in Malayalam, of the travel book Spices and Souls – A doodler’s journey through Kerala (DC Books, 2001) and of Santa and The Scribes – The Making Of Fort Kochi (Niyogi Books, 2014).

E.P. Unny is a celebrated Indian political cartoonist. After an education in sciences, he published his first cartoon in Shankar’s Weekly, in 1973. Four years later, he becomes professional, first with the Hindu, before working with The Economic Times, and finally The Indian Express Group, where he is currently Chief Political Cartoonist. He is the author of several graphic novels in Malayalam, of the travel book Spices and Souls – A doodler’s journey through Kerala (DC Books, 2001) and of Santa and The Scribes – The Making Of Fort Kochi (Niyogi Books, 2014).

Ravikant, bilingual historian, writer, and translator, chaired the lecture and moderated the discussion. Ravikant has been an integral part of the Sarai programme of CSDS (Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi). He has been coordinating projects on language, free software, and media, involving editorial, administrative, and intellectual engagements with the programme’s tech and Indic language networks. His current social history project, ‘Words in Motion Pictures’, navigates inter-media sites such as print, broadcasting, and web in an effort to offer creative connections between these media forms and their diverse publics.

© LILA Foundation

The lecture: Continuity is inherent to the cartoon art in its very dissemination. It functions from the temporal journalistic platform. The comic strip originated as Sunday funnies over a century back, in American newspapers, and the political cartoon migrated early to European newspapers. Both have since been serially read and must develop stakes in public memory. The news cartoon, bound to the unfolding of public life, invariably invokes the immediate past and suggests the near future. The comic strip which mostly sticks to the same ageless characters ought to create a still life but in practice builds up a continuum.

The lecture: Continuity is inherent to the cartoon art in its very dissemination. It functions from the temporal journalistic platform. The comic strip originated as Sunday funnies over a century back, in American newspapers, and the political cartoon migrated early to European newspapers. Both have since been serially read and must develop stakes in public memory. The news cartoon, bound to the unfolding of public life, invariably invokes the immediate past and suggests the near future. The comic strip which mostly sticks to the same ageless characters ought to create a still life but in practice builds up a continuum.

© LILA Foundation

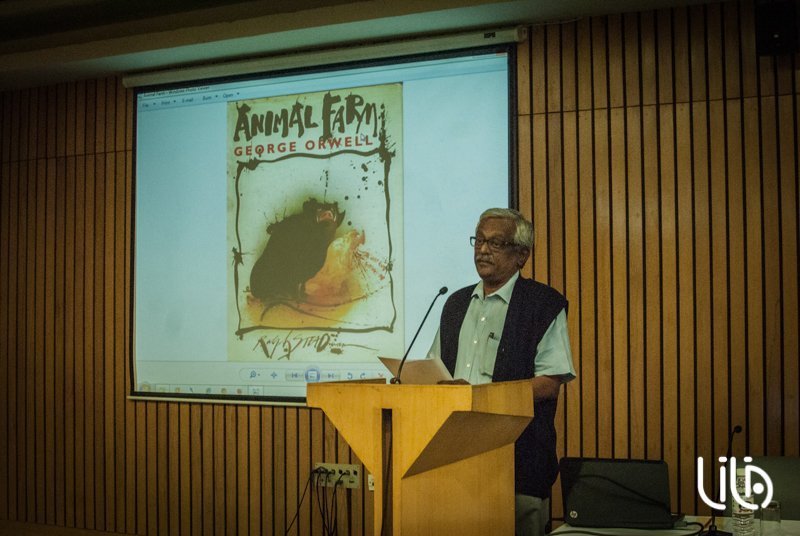

“The boy is with me every morning. In the middle of all the problems of our times, he brings me solace, happiness… and laughter!” Ravikant’s introductory words felt like the gratefulness of two entire generations – all those who woke up with EP Unny’s cartoons over the last four decades. A cardinal cultural figure was with us for the ninth PRISM Lecture of 2014, but yet, just like his Newspaper Boy, a celebrity hiding behind his subtle humour, his respectful wittiness, his shy smile. “I couldn’t write. I could draw,” recalled Unny of his decision to become a cartoonist. “So, tonight, I face an unusual problem… word count!”

The comic cartoon takes birth in the USA, in the first half of the past century. “Its purpose? To entertain.” Increasingly a vital ingredient of the newspaper, the cartoon soon enters its economy. “Initially, it was published to promote the paper, to bring audience. The cartoon creates characters – it permits characterisation.” And, through characterisation, an audience takes shape, following the daily remarks of this rather unique commentator. An early recurrent figure is Richard Outcault’s Yellow Kid, parodying high society antics. “With 20,000 cartoons, the Yellow Kid shows this art can become a rewarding career in the US.”

With the budding Counter Culture of the 1960-70s, several cartoon characters mature. “The cartoon permits continuity – starting with the continuity of characters. Some of them grow with their times. Their body ages. Their lifestyle changes.” And the comic enters India. Laxman, Abu and Ravi Shankar become the forefathers of the genre in the subcontinent. “Historical events reveal the role and the actual power of the political cartoon. Breakdowns are the real tests of the cartoon.” The Emergency imposes censorship. Certain media, like Shankar’s Weekly, where EP Unny drew his first cartoons in 1973, end up as casualties. “With the No Nehru of 1975, the No Mosque of 1992 and the No Tower of 2001, the real risks of discontinuity for the comic come to the surface.” New stratagems, new visual options must be found to continue the voice of subversion in spite of the taboos of each era. “There are some famous solutions. They rely on the most central figures of each political culture. Every time something goes really wrong in India, Gandhi appears in the cartoons. Just like Bill Mauldin’s Abraham Lincoln, weeping, bent over his hands the day after Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. It became such a strong symbol that the newspaper was mostly sold backside: the cartoon had become more meaningful than the headlines!”

The full house attending the talk engaged in a long session of questions and answers with the artist. “What makes Indian cartoon special? One aspect, certainly, has to do with the ethnic diversity of India. There are so many more politicians, and generally more kinds of faces to draw in such a country, so rough sketches cannot suffice. The Indian cartoonist must be subtler. Cartoon here is somehow graphically democratic!” Another question addressed the connection of the cartoon with Kerala. “It may have to do with our teashop culture,” Unny suggested. “Everybody is permanently commenting on political events. So, naturally, a number of politically inclined artists were meant to come out of this universe.” Responding to a query regarding the representation of women in the cartoon world, Unny ended with a note of optimism: “The last great act of the cartoon, for it to survive those breakdowns and reach continuity, is a new wave of young, powerful cartoonists. More women will have to come to the front of the genre. And I also sense that we will go towards more serialised content.” The attentive audience, blending friends of the first days and young admirers, enjoyed a rich and lively evening.

Samuel Buchoul