© LILA Foundation

Eddin Khoo is a poet, writer, translator, journalist and teacher. The Founder of the cultural organisation PUSAKA ~ Centre for Culture, Tradition, Ideas, he is the co-author of a book on traditional woodcarving entitled The Spirit of Wood. He is the author of several forthcoming books, including a collection of poetry All the World Figure, a scholarly study, Storm Clouds: Islam, Politics and Performance in a Malay State, a travel narrative, The Verandah of Mecca and a book of essays entitled The Muslim Predicament. His latest translation effort into the Malay language is Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman. His translations into English of the Indonesian poet Goenawan Mohamad and the Malaysian poet Latiff Mohidin will be published in 2015-2016. Eddin Khoo resides in Kuala Lumpur.

Eddin Khoo is a poet, writer, translator, journalist and teacher. The Founder of the cultural organisation PUSAKA ~ Centre for Culture, Tradition, Ideas, he is the co-author of a book on traditional woodcarving entitled The Spirit of Wood. He is the author of several forthcoming books, including a collection of poetry All the World Figure, a scholarly study, Storm Clouds: Islam, Politics and Performance in a Malay State, a travel narrative, The Verandah of Mecca and a book of essays entitled The Muslim Predicament. His latest translation effort into the Malay language is Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman. His translations into English of the Indonesian poet Goenawan Mohamad and the Malaysian poet Latiff Mohidin will be published in 2015-2016. Eddin Khoo resides in Kuala Lumpur.

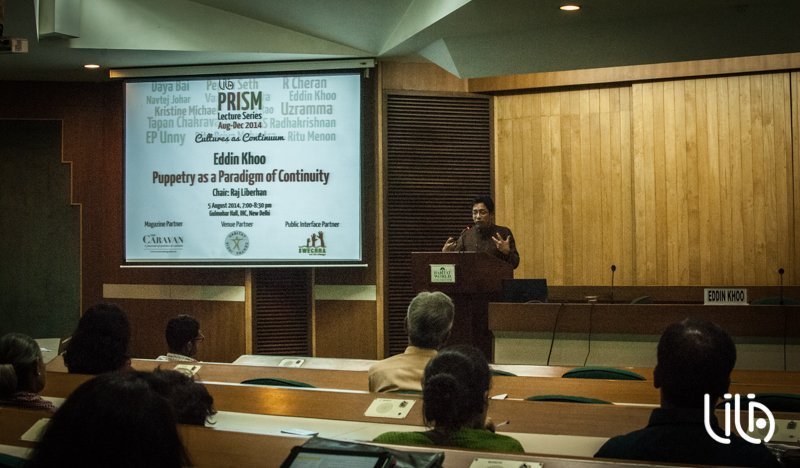

Raj Liberhan, the Director of India Habitat Centre (IHC), Delhi, chaired the lecture and moderated the discussion. He has held a significant range of responsibilities at the senior level in government, public sector and NGO environments, for more than four decades.

© Nithil Dennis

The lecture: Shadow puppetry is possibly the most distinctive performance tradition associated with Southeast Asia. Encapsulating within its narrative the diverse historical and religious influences that have shaped the cultural plinth of the region, the life of shadow puppetry has also undergone countless incarnations and exists today in ritual, folk, classical and popular forms. Puppetry as a Paradigm of Continuity traces the historical roots, practice and performance of puppetry within the Southeast Asian, and more particularly the Malaysian context. It explores the evolution of such principal epics as the Mahabharata and Ramayana within the Southeast Asian landscape, the role and purpose of ritual within the shadow puppet tradition as well as the vital and innate possibilities for reinvention that have ensured its continued practice, even as it encounters challenges to its viability by agencies of the modern state.

The lecture: Shadow puppetry is possibly the most distinctive performance tradition associated with Southeast Asia. Encapsulating within its narrative the diverse historical and religious influences that have shaped the cultural plinth of the region, the life of shadow puppetry has also undergone countless incarnations and exists today in ritual, folk, classical and popular forms. Puppetry as a Paradigm of Continuity traces the historical roots, practice and performance of puppetry within the Southeast Asian, and more particularly the Malaysian context. It explores the evolution of such principal epics as the Mahabharata and Ramayana within the Southeast Asian landscape, the role and purpose of ritual within the shadow puppet tradition as well as the vital and innate possibilities for reinvention that have ensured its continued practice, even as it encounters challenges to its viability by agencies of the modern state.

© Nithil Dennis

Puppetry, a paradigm of continuity. Why?

Opening the PRISM Lecture Series 2014 on Cultural Continuum with Malaysian cultural conservationist Eddin Khoo was a hint at the ambitious spatial and temporal scope of the debate. South East Asia is a cultural crossroad, echoing the multiplicity inherent in Indian traditions, and, in fact, often genealogically related to them. But, the spread of Sanskrit as the lingua franca of literature and the arts around the turn of the first millennium, or the simultaneous spread of Hinduism and Buddhism, should not reduce the region to a mere offspring of Indian cultures. What makes South East Asian culture, then? What is Malaysian culture? Eddin Khoo recalls the interrogation he offers to initiate with his students. “What is the Malay identity?” The only available answers are constitutional. Never cultural. A unified, common cultural history cannot easily be found. And it is precisely through culture, and through the multiplicity of cultures, that the concept of identity can be questioned. Through culture, the ubiquitous starting point of today’s political climates can be shaken.

But where is this culture to be found? When Eddin Khoo started to look at the traditions of Ramayanic shadow puppetry of North Malaysia, those practices were at the centre of a blind spot, attracting no public interest and receiving very less, if any, intellectual interpretation. At the heart of their practices, nonetheless, was the fabric of Malaysian culture, one of its most crucial body of influences, the content of today’s oft-praised ‘multiculturalism’. Looking at those ritualistic performances, one discovers the cracks between the clean lines of official histories. South East Asia did not just grow through a unilateral progression from animism to Hinduism-Buddhism and finally Islam, alongside the settling of Buddhism. Wars, conflicts, cultural encounters and economic exchanges had brought layers of unsuspected cultural subtleties.

The philosophical and spiritual teachings of those ritualistic traditions are truly fascinating. Ultimately, they contend that every person owns a certain kind of spirit, animated by 99 winds flowing through each of us. The Muslim motif of 99 is naturally found here. But in each person in particular, only two or three of these winds are dominant, and these come to construct one’s character, personality, temperament. But this individuality is compromised: the natural, innate self must be suppressed to live in wider communities. This is at the root of illness, depression, stress. And that is where the performance tradition comes in the picture. The performance is a space permitting release. Responses to particular types of music, of performance, of archetypes and characters allow the movements of winds, culminating in a temporary healing of the individual during the experience of trance.

On the one hand, we find this incredibly ambitious, spiritual outlook within popular traditions. And on the other, we observe today a very rigid, resistant political climate. In Malaysia, it takes the particular form of Muslim revivalism. The latter tends to impede on the space of the former. Politics eats, bit by bit, the heritage of our culture, because it breaks the dynamics of memory, of commemoration of memories. This is where culture becomes dangerous, subversive; this is where culture, and puppetry in particular, become models of continuity.

And this revival of political strongholds is directly related to multiculturalism. It is because questions of identity are so blurred in mixed cultures like Malaysia or Indonesia, that political ideology attempts a counter dynamics of forceful community differentiation. Post the 1970s, the modern project of secular nationalism had proven its limits. Finding one’s identity was an emergency. The Iranian revolution brought the desire, across the globe, to settle firmer Muslim identities. The Wahhabisation of certain Muslim communities implied a historicisation of Islam devoid of any cultural context. The political culture of the Sharia was set above everything else. Memory and history would not anymore be necessary: only the law is needed.

This movement came to influence Malaysia very deeply. The central Malaysian law would incorporate elements from these Muslim doctrines. It would even culminate in 1990 when the Islamic Party took over the northern state of Kelantan. Soon, all those traditions of ritualistic cultures would be banned and proscribed. The shadow puppet tradition was seen as Hindu, not Indian, and all its practitioners were polytheists and heretics. The power of single words in modernity: as soon as uttered, they enliven the public sphere. But few are those still eager to hear long, patient elaborations. Our attack on memory, on time, has reached that stage, too. Other performances, established around mythical stories centred on women, were also banned, because women should not be seen on stage. Kuala Lumpur would hardly respond to these regional developments. Since Independence, culture has been at best institutionalised, in museums, official performances, etc. But this bureaucratisation of culture did not contribute to the real appraisal of culture. It could not counter the bans and proscriptions. It could not stop the attempt to make of today’s generation one that lacks memory. Without memory, only one thing is left: politics.

How can we respond to such a scenario? Perhaps, we need to continue exploring culture, exploring our memories, to find in them the answers to these very questions. We must learn from politics to contribute to the power of culture as a subtle but extremely powerful means to subvert laws and dictums. Culture, theatre, art, performance, music, poetry are never just entertainment. They are a yearning. And through their silent survival, another need remains and is slowly coming back to the surface: the quest for a bigger, deeper history, for a more meaningful sense of our self. And it is in continuity, through culture, that this meaning can reach us.

Samuel Buchoul