© Guillaume Gandelin for LILA Foundation

Tuesday 10th, December 2013 – India Habitat Centre

Anil K Gupta is Professor at Indian Institute of Management (Ahmedabad), Executive Vice Chair of National Innovation Foundation, Founder of Honey Bee Network, SRISTI and GIAN, Fellow of The World Academy of Art and Science (California 2001) and Member of the National Innovation Council. His mission is to expand the global as well as local space for grassroots and young innovators to ensure recognition, respect and reward for them; to ensure the protection of intellectual property rights of the innovators; to explore ethical issues in conservation and prospecting of biodiversity; to link innovations, investments and enterprise; and to create knowledge network at different levels for augmenting grassroots green inventions and innovations in informal and formal sector. He aims at supporting social innovations in public and private sectors to expand entrepreneurial opportunities for disadvantaged people, and to strengthen the pursuit of authenticity in public life. He teaches Globalizing and Resurgent India through Innovative Transformation (GRIT), Shodhyatra (learning walk in Himalayan region), Creativity, Innovation, Knowledge network and Entrepreneurship (CINE), Strategic management of intellectual property rights including open source innovations (SMIPR), and doctoral level courses viz., Institution Building (IB), Agri Management (AM II), among others. Prof. Gupta was conferred Doctor of Letters from Central University of Orissa and Honey Bee Network received the Hermes Award (European Institute for Creative Strategies and Innovation, Paris, May 2012), apart from several national and international honours.

Anil K Gupta is Professor at Indian Institute of Management (Ahmedabad), Executive Vice Chair of National Innovation Foundation, Founder of Honey Bee Network, SRISTI and GIAN, Fellow of The World Academy of Art and Science (California 2001) and Member of the National Innovation Council. His mission is to expand the global as well as local space for grassroots and young innovators to ensure recognition, respect and reward for them; to ensure the protection of intellectual property rights of the innovators; to explore ethical issues in conservation and prospecting of biodiversity; to link innovations, investments and enterprise; and to create knowledge network at different levels for augmenting grassroots green inventions and innovations in informal and formal sector. He aims at supporting social innovations in public and private sectors to expand entrepreneurial opportunities for disadvantaged people, and to strengthen the pursuit of authenticity in public life. He teaches Globalizing and Resurgent India through Innovative Transformation (GRIT), Shodhyatra (learning walk in Himalayan region), Creativity, Innovation, Knowledge network and Entrepreneurship (CINE), Strategic management of intellectual property rights including open source innovations (SMIPR), and doctoral level courses viz., Institution Building (IB), Agri Management (AM II), among others. Prof. Gupta was conferred Doctor of Letters from Central University of Orissa and Honey Bee Network received the Hermes Award (European Institute for Creative Strategies and Innovation, Paris, May 2012), apart from several national and international honours.

Discussants:

Dr T Ramasami, currently Secretary to the Government of India, Department of Science and Technology, holds a Master’s degree in Leather Technology from the University of Madras, India and PhD in Chemistry from the University of Leeds, UK. He has also worked on energy research in Ames Laboratory Iowa, USA and on electron transport phenomena in the Wayne State University, USA prior to returning to India for undertaking his scientific career. He joined the Central Leather Research Institute, Chennai as a scientist in 1984 and served as its Director for more than 10 years during the period up to May 2006.

Dr. Kavita Sharma is the Director of India International Centre since 2008. She was the Principal of Hindu College and has the distinction of being the first woman Principal of a co-educational institution in the Delhi University. She is a member of the Executive Committee of Delhi University. She holds a doctorate in English from Delhi University and has written and published extensively, with about half a dozen single author books to her credit. Her published research articles in reputed journals cover a wide range of subjects such as Education, Literature, Theatre and gender issues. Dr. Sharma has received several fellowships and awards. Notable among these are Fullbright New Century Scholar for the year 2007-2008, Faculty Research Fellowship and Faculty Enrichment Fellowship by the Shastri Indo Canadian Institute in the years 1991-92 and 2002-03 respectively.

© Guillaume Gandelin for LILA Foundation

The Lecture: “India Reimagined, Redefined and Reignited: A perspective on the grassroots, youthful creativity and innovation” discusses how India is constantly redefined by the forces contesting for domination of mind space, cultural scape and memoryscape. The more privileged one is, the more cynical one becomes. It seems that sustaining hope and reinforcing faith is a project undertaken by knowledge rich-economically poor people. This lecture will share ideas and insights gathered from shodhyatras (learning walks) throughout the country along with other volunteers of Honey Bee Network during the last 25 years, though in particular 16 years. One may ask why the image of the Indian society is so optimistic and reassuring when seen from the perspective of unaided, grassroots achievers, innovators and traditional knowledge holders. And yet why are the state and its various institutions so hesitant in engaging with these creative people? Perhaps, there is the fear of upsetting the apple cart, and their own imagination about the backward, unthinking working class at the grassroots? I will critique public policies which treat people as having only legs, mouth and hands, but no head, as attempted in the largest employment program MGNREGS. The idea of treating people as only a sink of assistance aid and advice, rather than sources of ideas, imagination and institutional vibrancy will be challenged herein. The experience at the Honey Bee Network, Sristi and Techpedia.in, GIAN (Grassroots Innovation Augmentation Network), and National Innovation Foundation, will of course be the backbone of the presentation.

The Lecture: “India Reimagined, Redefined and Reignited: A perspective on the grassroots, youthful creativity and innovation” discusses how India is constantly redefined by the forces contesting for domination of mind space, cultural scape and memoryscape. The more privileged one is, the more cynical one becomes. It seems that sustaining hope and reinforcing faith is a project undertaken by knowledge rich-economically poor people. This lecture will share ideas and insights gathered from shodhyatras (learning walks) throughout the country along with other volunteers of Honey Bee Network during the last 25 years, though in particular 16 years. One may ask why the image of the Indian society is so optimistic and reassuring when seen from the perspective of unaided, grassroots achievers, innovators and traditional knowledge holders. And yet why are the state and its various institutions so hesitant in engaging with these creative people? Perhaps, there is the fear of upsetting the apple cart, and their own imagination about the backward, unthinking working class at the grassroots? I will critique public policies which treat people as having only legs, mouth and hands, but no head, as attempted in the largest employment program MGNREGS. The idea of treating people as only a sink of assistance aid and advice, rather than sources of ideas, imagination and institutional vibrancy will be challenged herein. The experience at the Honey Bee Network, Sristi and Techpedia.in, GIAN (Grassroots Innovation Augmentation Network), and National Innovation Foundation, will of course be the backbone of the presentation.

© Guillaume Gandelin for LILA Foundation

Minds on the margin are not marginal minds. Faithful to his inimitable energy, Anil Gupta’s lecture for the PRISM series enthralled a full house, captivated by the relevance and the originality of the activist’s discourse. It is an energy that is always aware of the challenge ahead of us: Anil Gupta acknowledged that National Innovation Foundation has ‘only’ reached 0.18 million people. Indeed, there is much more to do. But we are in an era open to such major endeavors: if India must be redefined, reimagined, reignited, it is also because all over the world, more and more populations have recently discovered that, in addition to their voice, they also have the power to create new categories to articulate their choices, their beliefs, their aspirations. The method must become a communicator of the message.

The goal of the Honey Bee Network has been, since day one, to focus on those people who have not been given their chance in the ‘official’ spheres. There is a huge amount of work that can be done by connecting formal and informal spheres of work. This does not just mean bringing the formal into the informal: while we often see the urban knowledge authorities going to teach rural communities, we must modestly go the grassroots and learn from the artisans, the workers, the farmers, etc. Just as in other parts of the world, rural communities have been developing very refined traditions of technological inventions. With the recent urban growth of India, this cultural wealth has been put to the background.

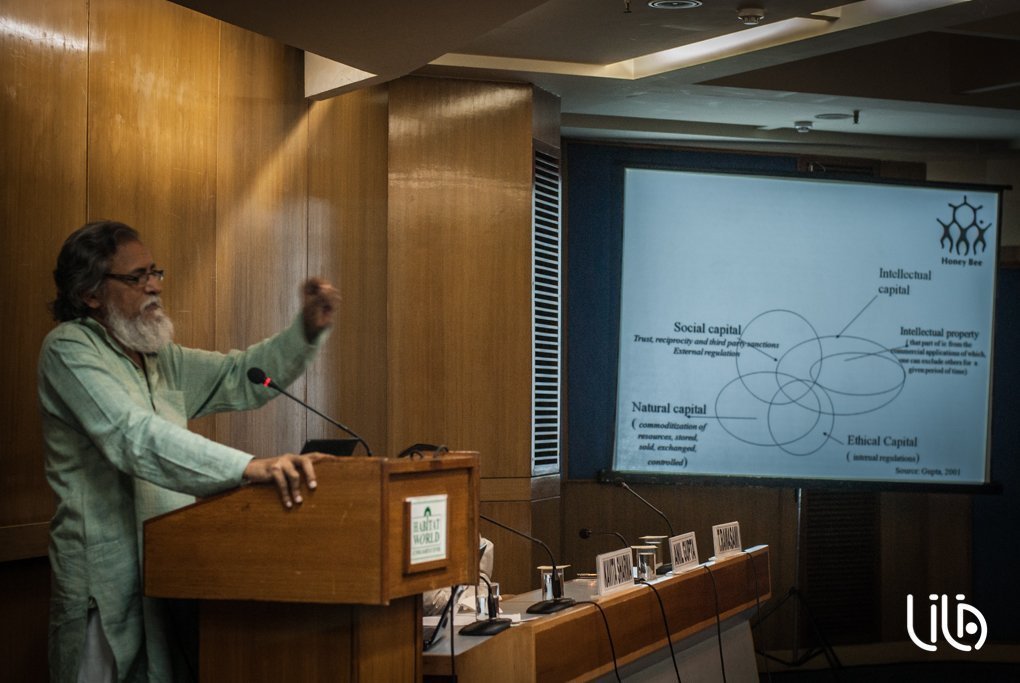

Playing a central role in this grassroots efficiency is what Anil Gupta called the ‘ethical capital’. While most institutional systems in the so-called ‘developed’ urban settings are reward-based and regulated through strict, external restrictions and norms, we must also develop new models that rely upon the ethical capital. For instance, in every part of the world, when fish swim up north to lay their eggs, fishing them is a taboo. These are norms of self-regulation.

The prevalent models of innovations today emerge through five types of tensions:

- Autonomy vs. agency: we should not only have the freedom to act but also have a democratic, equitable framework from which to act.

- Accuracy vs. affordability: should we always privilege a Rs. 10000/month medicine with 99% efficiency or a Rs. 100/month one with 80% proven efficiency and no side effects? Besides, does not it make better ecological sense to leave the body to work out its own natural healing system than providing full external medical support, except in the case of life-threatening conditions?

- Blueprint vs. autopoiesis: how to create institutional models that are strong in their current programme as well as capable of evolving through processes of self-correcting and self-designing?

- Institution -based innovations vs. user-led innovations: more and more corporations and institutions are opening themselves to receive innovations from practitioners and users—doctors, as they practice, arrive at a lot of useful innovations which are not institutionally sanctioned.

- Symmetrical vs. asymmetrical open innovation models: in this heterogeneous country, should we maintain a non-pluralistic and copyright-based economy of innovations as found in the West today?

When innovations are designed, three dimensions must enter into our consideration: affordability, accessibility, availability. A bag of rice may be affordable to me, and the shop, accessible, but is it available? An efficient innovation can only happen if the three conditions are satisfied. But innovations are not rare. In fact, everyone can start one. All that needs to be done is adding one new feature to any of the three aspects of the innovation: material, method and user or applicant. For instance, one may take an aspirin that is already created, through an accepted method, but use it for thinning blood. That’s an innovation at the application level. We witness such democratization of innovations today.

Naturally, an innovation is remarkable when it is budget-friendly, when it also ends up as a viable economic plan. In other words, innovations follow imperatives of frugality. Frugality must be followed at the same levels: material, method and application. For instance, one could think of the frugal workplace of watch repairers on the side of our streets. They also represent models of concentration: they remain absolutely undisturbed by the surrounding noise. In passing, Anil Gupta suggested that we could find inspiration in them for us, too, to remain undisturbed by the everyday noise of social as well as classical media… But frugality has always been in the Indian Samskara. Many youngsters in the new generations think there is enough to waste, enough to consume. How did this happen? The point here is not to voluntarily create physical lack, but rather to try developing a mental awareness of frugality.

This spirit of frugality is not what we call in India the jugaad, the makeshift. That is only passing around the problem, and not solving it. It is lazy intellectualism. Authentic innovations are the product of genuine thinking processes. We can learn from them at four levels, from the concrete to the abstract: at the artefactual level, by replicating similar designs; at the analogic level, by using the innovation as a metaphorical inspiration, at the heuristic level, when the innovation reveals a new model of thinking, and finally at the gestalt level, when it highlights new configurations of the factors in place. Anil Gupta mentioned an example he came across: in a village, he and his team found a series of terracotta figures of horses, under a tree. They were told that these were kept there not as decorations, but to serve as models of excellence for the children walking by. This kind of practice sets standards much more efficiently than what we have in our ‘developed’, urban systems and institutions.

If there is one site where frugality has not been a priority, it is time. But there are communities that have worked out effective means of tackling time. One of the most impressive innovations Anil Gupta came across was a Rs. 5000 windmill used to irrigate paddy fields. The irrigation takes more time with this device– 48 hours instead of 4, but in fact plants need moisture, and not water. Even nature prefers things that are done patiently, through time. In a way, as Kavita Sharma pointed out in her response later, even in allopathic medicine it is acknowledged that the body cures better when prescriptions are spread across time.

Innovations must also adapt to the actual uses. The windmill example illustrates that: there is no need of so much water at once. In Jalgaon, Maharashtra, Anil Gupta’s team came across a scooter-based washing machine. Similarly, a scooter-mounted flourmill was created to custom-serve users who have lesser requirements. When the technology is set on the parameters of each user, the system changes.

Anil Gupta also mentioned the G2G projects: Grassroot to Global. Grassroot innovations now encounter a global market. For many other projects too, the buyers come by themselves to find the innovators. Our grassroots innovations can not only benefit India, but our globalised societies as well. Anil Gupta also contributed to developing new economical models for the formal industry. For instance, TATA Agrico commercializes a model of sugarcane bud-chipper that is manufactured in the village of its creation.

The discourse surrounding the field of innovations is naturally primordial. One recurring question concerns the portfolio of incentives for innovation. It emerges on the backdrop of a market that is supposed to satisfy all our needs and desires. But which market are we talking about? Economy does not have the monopoly of markets: there is also the market of emotions, of interpersonal relations, of family, of communities, etc. In this context, incentives do not have to be only material. We also know that regularly, when the incentives are increased, the productivity actually decreases.

Grassroots innovations cannot solve all problems. But they can solve some. Moreover, many innovations take place without an understanding of the reasons behind the problems. This is where we still need scientists, philosophers, or the industry to complete the process. Grassroots innovations can work hand in hand with the formal sectors.In her response to the lecture, Kavita Sharma, Director of India International Centre, connected Anil Gupta’s insight with her original field of activity: higher education. She argued that, in Indian universities, the idea of modernization has been irremediably associated with the West. But the western project and its ethos aim at a homogenous cultural model, which is hardly applicable in India. India has other identities, other mythologies, other cosmologies.

Nonetheless, today, we still think and talk in western terms: we contend that 90% of Indians are ‘uneducated’, but this is a very narrow definition for education. These are highly educated populations. They are far more skilled than most of the ‘officially’ educated populations. We have to build an eco-model that has room for both.

In new paradigms, we have to emphasize cultural identity. For instance, this implies studying Indian English authors in departments of English Literature. And the students are always more receptive to them: they speak of a reality they know! Moreover, if we work at a closer level of proximity, that is, when we enter the community bases, the self-reliance of an individual will be more effective. A community is aware of its strengths and weaknesses, in social life but also for instance in ecological matters. There, the ‘ethical capital’ mentioned by Anil Gupta is more central. It will also lead to encourage research usable for our communities, and not just what it has been, till date: a response to already existing academic problems, most of which set in the west. According to Kavita Sharma, we have to get out of the enlightenment agenda. This is possible not through bringing the ‘under-developed’ in the comfort zone of the ‘educated quotas’, but by understanding the diversity of identities and communities.

After a few lively exchanges with the audience, T. Ramasami, Secretary for the Government to the Department of Science and Technology, closed the evening. Reformulating the challenges mentioned through the lecture, Ramasami emphasized on those specificities that Indian culture must rely upon to develop a new understanding of innovations. For instance, he argued that Indians are ‘obsessive optimists’. For Ramasami, a pessimist is a person who sits in front of a cashew nuts and pastries, and thinks only about one thing: calories. An incredibly inspired creativity is another strength of Indian culture. Ramasami related how he learnt science from a school that did not have any lab. The teacher had asked the students to go and collect a leaf each. Everyone had to write a page about what they could observe. The pupils came up with a variety of observations. This led the teacher to give a lot of information on the nature and mechanisms of plant life, which surpassed the standard quantity and depth of teaching for this age. Lastly, returning to the title of the evening, Ramasami argued that the good thing about India, it is that it is not definable. More than a country or a nation, India is a civilization. And it is a virtue that India cannot be standardized.

Sankalp Sharma

Great to read the thoughts of Prof. Gupta once more. I would like to congratulate him on his indefatigable determination to not only understand India’s traditional innovation systems but also his deep enquiry into understanding the minds behind the innovations. I feel people like him need to be, not only encouraged but emulated. Also I would congratulate LILA for organizing such wonderful evenings for people of Delhi. Great initiative.